Danny Moynihan’s Landscapes Look Back at Us

I first met the multitalented Danny Moynihan within the early 1980s, however I didn’t see him once more till not too long ago. During that point, he’s labored as a gallerist and an impartial curator, printed a satirical novel in regards to the artwork world (Boogie-Woogie, 2014) and a collection of his assortment of erotic pictures (Private Collection: A History of Erotic Photography, 1850–1940, 2014), written An Installation for Agongo, an opera, and exhibited his work in England and Los Angeles (which I used to be solely capable of see in copy). Because I felt strongly about his work once I noticed them within the 1980s, early in his profession, I used to be notably curious to see In Praise of Limestone at Nathalie Karg Gallery, his first solo exhibition in New York. I knew his work had modified, however I wasn’t certain how.

The exhibition’s title comes from one among W. H. Auden’s best poems. In a letter to his biographer, Edward Mendelson, Auden wrote of limestone “that rock creates the only human landscape.” I point out this as a result of Moynihan’s work, which start with direct statement of various landscapes visited by Paul Cézanne, invite allegorical readings, however with a twist. The hidden that means of his photos, which meld human and nonhuman kinds with rocky landscapes, stays opaque. They are invitingly impenetrable, whilst they fire up all kinds of associations, from mythological beginnings to rampant lust and greed.

While the exhibition’s 10 work primarily depict rocky landscapes, each has its personal character. Since one of many present’s underlying themes is the connection between a human physique and an detached panorama, discovering alternative ways to convey that trade was one among Moynihan’s challenges, together with making every panorama particular and distinct from the others.

In “Quarry” (2021–22), which takes Cézanne’s depictions of Bibémus Quarry as a place to begin, dinosaur bones merge with giant tough stones, and collectively evoke the physique and flesh. It is that this ambiguity that held my consideration. Are we trying at stones or buttocks? The tough areas can counsel scar tissue or wounds, including one other layer of that means to the work.

By reminding us that we dwell on a planet that has been residence to innumerable different animals, lots of that are lengthy extinct, Moynihan frames the current inside an expansive stretch of time. By imbuing a few of the stones with a fleshy presence that ranges from youthful to decaying, he provides one other a measure of time. The sky above the land that speaks to those two measures of time provides one more sense of time, underscoring our insignificant existence in an detached universe. I believe this understanding of time’s disdain for humankind and the myths we derive from the rocks and soil of the earth — whether or not they are often up to date and remodeled with out dropping their primal energy — are on the artist’s thoughts.

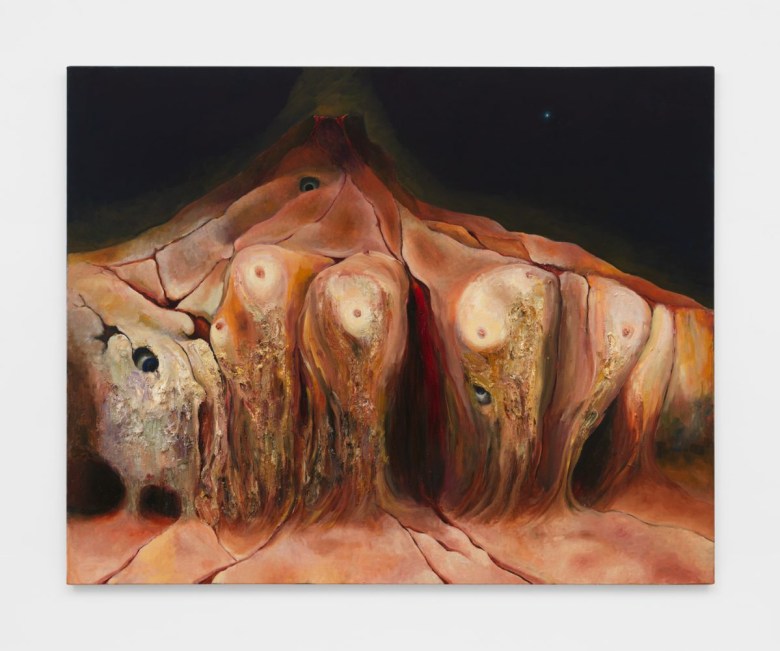

The contour of the mountain in “Gaia” (2021–22) resembles Paul Cézanne’s Mont Saint-Victoire, however Moynihan has remodeled it right into a volcano. An irregular row of huge, different-sized, orb-like shapes protruding from the foot of the mountain is animated by the Cyclopean eyes that appear to stare again at us. They belong to creatures we can not see. What are we to make of them? And, equally necessary, what do they make of us? The work attracts out a sense of mutual estrangement on account of our incapacity to see the whole creature.

“Charge” (2021–24) is the one portray populated by lively creatures, which resemble pigs. The two on the left facet of the work are licking and nuzzling what appears to be an unidentifiable milky white creature, just like the only one on the fitting. Behind them is a formation of porous limestone from which staring eyes might be seen. The juxtaposition of eyeless porcine figures and bodiless eyes, gentle flesh and porous rocks, suggests the alienation of thoughts and physique, rational considering and animal greed. Is lust an impulse that we are able to management? What can we do in regards to the greed of the tremendous wealthy? How does their greed have an effect on us and the earth we share?

By starting with motifs impressed by Cézanne, is Moynihan charting how far now we have devolved because the single-minded French painter who walked for miles in pursuit of the right view of diffident nature? What does it imply to animate the stones with flesh and eyes? There are not any straightforward solutions to the questions that come up in these work.

Danny Moynihan: In Praise of Limestone continues at Nathalie Karg Gallery (127 Elizabeth Street, Lower East Side, Manhattan) via December 20. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.