The Diasporic Imagination of Nishan Kazazian

This article is an element of Hyperallergic’s 2024 Pride Month sequence, that includes interviews with art-world queer and trans elders all through June.

Nishan Kazazian has been half of my life in some type since I arrived in New York City roughly 25 years in the past. He’s a uncommon older homosexual SWANA American who has saved his connections to varied communities, whether or not ethnic, cultural, or sexual, and embraced the typically irritating realities of that lived complexity.

An artist, architect, and designer, Kazazian’s life in Beirut earlier than the Civil War was wealthy. He was even taught as a baby by famend artist Paul Guiragossian, who was one of his grade college artwork lecturers. When I requested him about that have, he joked that every one the aged artist did was sit within the classroom and let the scholars do what they wished, so Nishan did precisely that, and has finished so ever since.

During these childhood, he not solely created summary artwork that was exhibited at distinguished venues within the nation, together with the Sursock Museum, however he would interview older Lebanese Armenian artisans about their lives and cultural traditions pre-Armenian Genocide, train artwork to incarcerated younger ladies in Beirut, and a lot extra. His polyglot observe was on full show earlier than he even left Lebanon.

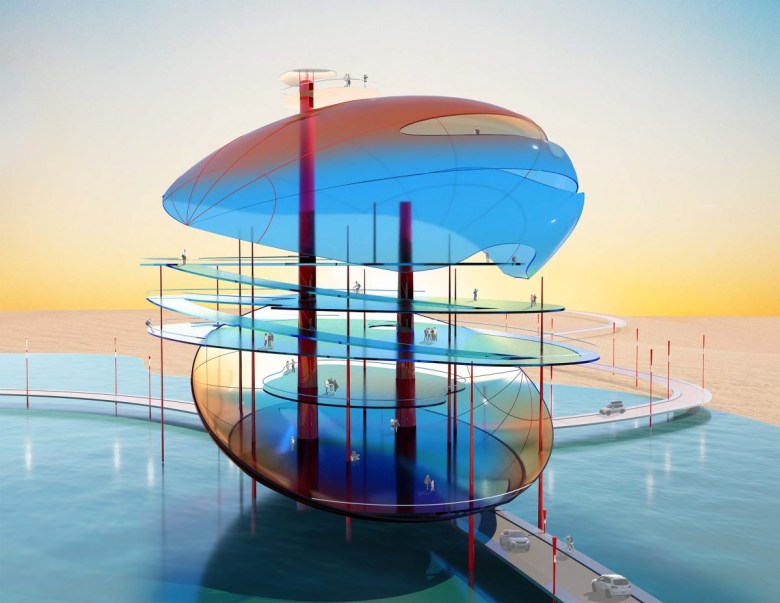

In New York, the place he ultimately settled after Lebanon, Kazazian’s observe turned to be extra research-based, and his paper structure, although at some point I hope some of these can be constructed, has flourished to include his reflection on migration, diaspora, trauma, violence, and dialogue. As an artist, he’s all in favour of layering and complexity, creating objects that draw back from focal factors, preferring to linger on the methods types and planes match collectively, even when awkwardly, an apt metaphor for displacement and discovering house.

Among his achievements, Nishan has constructed a house in New York together with his accomplice, Jack Drescher, a distinguished psychoanalyst identified for his work on sexual orientation and gender id. I’ve had the great fortune of being in his orbit, studying from him in regards to the layers of id that we frequently wrestle with and the impacts these can have on our lives, relationships, and work. I wished to honor Nishan’s contributions to my life and communities with this profile, and he was type sufficient to share his solutions with us.

* * *

Hyperallergic: When did you come out?

Nishan Kazazian: First, I want to thanks and Hyperallergic for considering of me and together with me. As you already know, initially, I mentioned no, however then I considered it and determined to say sure. The cause I first mentioned no was that I by no means wished to be categorized or labeled based mostly on my sexuality or age. However, I’m conscious that, now greater than ever, with the intention to “belong” or be seen or be taken “seriously,” one has to suit right into a class. Times have modified and categorizing has turn out to be the norm.

In phrases of my sexuality, I used to be by no means “in the closet,” so I didn’t must “come out.” My grownup sexual id was at all times a form of delicate negotiation, relying on place and time — testing the waters, contemplating folks’s taboos and biases, and making them perceive who I used to be. Some selected to disregard the alerts; some selected to embrace them; some had been in denial; and a few had been outraged. Incidentally, straight males have at all times been my greatest associates, notably those that had been safe of their sexuality or those that had a detailed member of the family or one other good buddy who was homosexual.

Further, within the late seventies after I had utilized to remain within the US after graduate college at Columbia University, the immigration and naturalization service would reject an individual’s utility in the event that they had been overtly out, so navigating these waters was essential.

H: Has the artwork neighborhood felt open to you? Have you discovered it accepting?

NZ: Being born in Beirut and having lived in Europe after which most of my life in New York City, the acceptance I’ve skilled has assorted and shifted over time and place. I don’t assume my sexuality has had any affect on my discovering acceptance in an inventive circle, no less than not that I’m conscious of. However, my artwork and structure practices have performed a task during which circles I discover extra acceptance. I’ve been advised overtly by one facet, “But you are an architect,” and by the architectural facet, “You are more an artist,” although I’m a New York State licensed architect and most of my training was in high quality arts. Some of this may very well be the consequence of a number of underlying elements.

I can assume of one incident that captures this dilemma. I bear in mind a gallery proprietor who admired my work, but saying, “But why are you doing art? You make more money doing architecture. Besides, my clients will not want to buy art created by an architect.” So, figuring out myself has been an ongoing course of of attempting to not be boxed in by others. In my life, I’ve at all times wished to keep away from that and create issues exterior the field.

H: Who do you think about your mentors? Did you’ve got queer mentors if you wanted them?

NZ: First, my maternal grandmother. My grandmother’s tales as a younger baby had been profoundly influential. I bear in mind her telling Armenian fairy tales about kings and queens, good and evil, palaces, goals, and miracles. The Good at all times triumphed in the long run, and each one of her tales concluded with, “and three apples fell from the sky, one for you, one for me, and one for the storyteller.”

Second, Dr. Harry Van Mierlo, who got here from a distinguished Dutch household that resisted the Nazis throughout World War II, considerably affected my life. His encounters, resistance, resilience, challenges, and braveness had been inspiring. He was in Beirut at Haigazian University, instructing psychology whereas serving to Palestinian refugees and, via his worldwide connections, additionally saving Jewish lives in Iraq. His philosophical lifestyle and wars, in addition to his ebook “Power and Manipulation” about world politics, profoundly formed my understanding of how issues actually work.

Third, Prof. Arthur Frick, an artwork instructor on the American University of Beirut. Frick, my artwork instructor, had an enchanting journey, from service within the US Army in Japan to changing into an artist and artwork instructor. Beyond his method to artwork — and my artworks specifically — he typically expressed remorse about not having turn out to be an architect. His mentorship influenced me to pursue structure, guaranteeing that I’d not have related regrets.

Fourth, Prof. Bill Mahoney at Teacher’s College, Columbia University. Prof. Mahoney, whose ceramics items and discussions about artwork, ceramics, and structure had been immensely helpful, additionally regretted not changing into an architect. He too strengthened my determination to check structure, to combine artwork and structure in public areas and to keep away from future regrets, irrespective of how profitable I used to be in my art work.

Fifth, Professor Klaus Herdeg at Columbia University’s GSAPP, whose analysis and documentation of Indian stepwells and Islamic structure in Isfahan, Iran, inspired me to do my thesis venture on New Julfa, Isfahan. Under his mentorship, I built-in the cultural and social components influencing Middle Eastern and Western approaches in structure. From him I discovered that concepts “travel” and diffuse into new meanings and types.

And concerning Queer Mentors. No, I didn’t particularly have queer mentors that I recall. However, I did have homosexual associates with whom there have been supportive interactions. In hindsight, maybe I by no means wished a mentor of any type. I most popular to listen to tales from folks, whether or not homosexual or straight, ladies and men and take from their narratives what I discovered helpful in phrases of the place I wished to go.

H: How, if in any respect, does your id issue into your work? How would you describe the position it performs?

NZ: I grew up in a multicultural, multi-ethnic, multi-religious, and multilingual Beirut, surrounded by an beautiful topography of mountains and sea, with layers upon layers of archaeology, in addition to trendy structure and facilities. Since 1973, I’ve lived in NYC and, for some time, in Boston.

I additionally grew up in a household in an space populated by Armenian Genocide survivors, with most of my prolonged household scattered world wide. Witnessing Their resilience, endurance, adaptability and inventiveness taught me to by no means hand over. In reality, one of my earliest works, whereas I used to be nonetheless in highschool in Beirut, was titled “Doomsday, Diaspora and Rejuvenation.” It was exhibited in a juried present on the Salon d’Automne on the Sursock Museum in 1968 and, trying again, I consider that early work predicted the trail I charted.

Since my highschool years, my art work has at all times mirrored themes of separation and connection, belonging and never belonging, and the need to belong. Yet, I additionally wished to be completely different, to do issues in another way. This has been true since my early days in highschool, via faculty, and ever since.

In addition, I establish as a minority inside a minority on a number of ranges. I’m Lebanese-Armenian-American, homosexual. I dwell in New York with a distinguished Jewish psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, Dr. Jack Drescher, whose worldwide contributions on gender and sexuality have profoundly formed up to date understanding and acceptance. I’ve been impressed to embrace and combine the various views of all these layers into my work.

My multi-layered exposures and experiences have fostered a sure id expressed via and in my works. Creating these works has helped me navigate the curler coaster of life, reworking life expertise into artwork, experimental structure, and imagined futures.

H: What’s a queer art work that’s essential to you?

NZ: I’m an incredible admirer of the work of Keith Haring who was identified for his beneficiant contributions to public areas. I personally witnessed him portray in subway stations, vehicles, and numerous different areas. With his daring, energetic traces and vibrant colours, he aimed to problem societal norms and promote inclusivity. He additionally demonstrated a exceptional and admirable disregard for monetary achieve, as a substitute specializing in enriching communal environments. His transformative artwork turned bleak areas into vibrant celebrations, leaving a permanent legacy of creativity and altruism.

I additionally admire Frida Kahlo; Her bisexuality, her exploring themes of id, gender, and sexuality, alongside her unwavering resilience in confronting her well being challenges. All of that is evident in her dedication to color regardless of HER bodily limitations, as she reworked her ache into highly effective expressions of artwork.

As a licensed and training architect, I discover Philip Johnson’s iconic Glass House to be a compelling metaphor for openness and visibility, embodying his modern design philosophy and spatial ideas.

Another supply of inspiration for me has been Sergei Parajanov, the Soviet Armenian-Georgian artist and filmmaker. His motion pictures eloquently painting the various cultures of the Caucasus, encompassing Armenian, Georgian, Azerbaijani, Russian, and Ukrainian heritages. Despite going through challenges stemming from his sexuality, Parajanov’s unwavering dedication and resilience are evident in his work. Through intricate tableaux of historical past, archaeology, and intercultural narratives, his movies weave collectively visible poetry that evokes deep emotional and cultural resonance.

H: What does Pride Month imply to you?

NZ: Pride Month means celebrating variety and solidarity with deprived and unvoiced communities, acknowledging how far we’ve come, and recognizing the journey that also lies forward.

H: What are you engaged on now?

NZ: I’m presently engaged on a number of artworks in acrylic and sustainable wooden veneer constructions. Additionally, my most gratifying works are sometimes the consequence of unintended outcomes, reminiscent of my current Plexiglass and acrylic paint construction, “Transient Shadows: Unyielding and Defiant,” and a sustainable wooden development titled “Revamping Lost Horizons.”

I’m additionally finishing an modern architectural set up referred to as the “Alternative Zoo.” This venture makes use of Wi-Fi, drones, and cameras to venture dwell imagery from native habitats onto site-specific architectural types. The Alternative Zoo goals to keep away from the outdated cruelty inherent in conventional zoos by offering a humane and immersive expertise.

For me, it isn’t about reiterating messages we’re already conscious of, reminiscent of “Icebergs are melting,” neither is it merely about aesthetics. It is about taking it to a different stage—The work is about integrating expertise, imagining materiality, utilizing AI as a software reasonably than an finish, and creating works that function catalysts to deal with our existential challenges.

H: Do you are feeling linked to approaching queer artists and art work?

NZ: I hardly ever view an art work via the lens of it being “queer.” I choose to judge A bit based mostly by itself intrinsic qualities and my private connection to it. If I study that an artist identifies as queer they usually explicitly state this of their work, then I make an effort to know the context, background, and motivations behind their artwork. This deeper understanding helps me admire the distinctive views and experiences that inform their creations, however my major focus stays on the artwork itself and the way it resonates with me on a private stage.