The Comedians Who Helped Define Generation X

Last May Prime Video launched the sixth season of the legendary sketch comedy present The Kids in the Hall. Not a reboot, however a continuation following a 27-year hiatus. The 5 actor-comedians who make up the troupe — Dave Foley, Bruce McCulloch, Kevin McDonald, Mark McKinney, and Scott Thompson — are older and a few of their preoccupations have modified, as dying, which pervaded the unique sequence, creeps nearer and the era hole between the troupe and younger audiences widens. But to the aid of most critics and followers, they’re nonetheless outsiders wanting in at mainstream society with curiosity and contempt.

Anyone who had entry to the present when it premiered in 1989 on HBO and CBC present in KITH a set of values that rejected the established order with out ever partaking in gauche politicking. It wasn’t the form of righteous takedown that battled for cultural supremacy — and led the earlier era from antiwar protests to neoliberalism. It exploited society’s deep-seated perversity to show it in on itself. From the outset the troupe declared their allegiance with outsiders. These have been the parameters that followers may take or go away; and when you left them you most likely weren’t a fan. They have been unrelenting of their indictment of normative and patriarchal society. Their antipathy towards authority figures — notably fathers, cops, and businessmen — was counterbalanced by their empathy for anybody marginalized or disregarded: intercourse employees, circus freaks, and all the youngsters who got here from dysfunction. “It did feel like we weren’t like the rest of the people in the world,” Bruce McCulloch mentioned in a current Zoom dialog, forward of his reside solo present Tales of Bravery and Stupidity, and a troupe efficiency in Calgary on April 28.

When it started, The Kids within the Hall belonged to Generation X, not solely as a result of it comprised a lot of the present’s viewers, however as a result of the outsider standing, alterity, and existential angst that got here to outline Gen X was ingrained within the troupe’s DNA. The archetypal teenage Gen X-er within the early ’90s felt a heightened sense of insecurity, each existential and lived, that grew from the failure of the earlier era’s utopianism. At the time, the best divorce price in historical past left mother and father at work and youngsters at residence alone, fending for themselves earlier than they have been highschool age. We retreated into our worlds and, with a vacuum the place parental steering ought to have been, turned ideological agnostics. We sought out our personal worth system from the few enlightened adults round, whether or not in life or on TV — TV raised most of us, anyway.

The cynicism that underlay your entire sequence was each a mirrored image of and a response to the zeitgeist. KITH displayed a singular grasp of what it feels prefer to be set adrift in an period outlined by uncertainty. In a transfer that may be exceptional for many comedians, they didn’t chase after laughs, or they sought them from a spot of disquiet: In a sketch titled “B&K,” for instance, a vaudeville duo descend into more and more grim dialogue, starting from infidelity to midlife disaster to abortion, earlier than breaking right into a music and dance; in “Mass Murderer,” a serial killer bemoans his job rut; and within the traditional “Citizen Kane,” a disagreement a couple of film title escalates right into a brutal homicide.

The troupe’s 1996 movie Brain Candy begins with this aphorism: “Life is short, life is shit, and soon it will be over.”

But their cynicism was embedded in a self-contained aesthetic and conceptual world rife with nods to avant-garde movie and artwork, and underground tradition. The troupe’s preternatural capacity to reflect and join with their viewers, and to articulate it by way of their imaginative and prescient, in flip gave the viewers the instruments to formulate their very own countercultural beliefs. In a mid-2000s commentary for the 1988 pilot, Scott summed up the present’s sensibility as “teen rebellion, drag, and perverse sexuality.” In the early ’90s, KITH transgressed boundaries of propriety, gender, sexuality, even species as a substitute for binary considering.

The troupe’s pivotal contribution to this was their centering of queer characters and themes. The present each normalized LGBTQ+ life and addressed taboo points, from the AIDS disaster to homosexual marriage and parenting, principally led by Scott, the troupe’s solely homosexual member, and his philosopher-provocateur alter ego, Buddy Cole — whose monologues affirmed the present’s queer-positive stance and have been the closest it got here to direct political engagement. But your entire troupe took half in refusing the male heteronormative mode typical of sketch comedy and the rampant homophobia of 1980s and ’90s comedy normally.

In “Scott’s Not Gay,” Scott comes out of the closet as straight to hordes of offended followers. A confused Bruce asks, “first you were gay … and now you’re un-gay?” — successfully making a world the place “straight” exists solely as an unnamed deviation from “gay.”

“It’s a rejection of the super macho heterosexuals that none of us could be even if we tried,” Bruce defined in our interview. “Sometimes people early on would say that we were a gay comedy troupe. And I didn’t mind that definition,” he added. “[At the time] I said, I think it’s more powerful if here I am, a kid who somehow wandered out of the cesspool that is [1970s homophobic] Calgary, Canada, and I’m embracing the things we’re talking about. And yeah, I’m kissing Scott Thompson on the lips, and Kevin too, and probably Mark and Dave as well, in the AIDS-ravaged ’80s.”

The sociopolitical floor the Kids broke and the dangers they took on this vein stay undervalued, whilst they’ve been slowly acknowledged over time. But the troupe established their road cred by clubbing with drag queens within the opening credit; queering heteronormative movie and TV tropes; and inhabiting characters who appeared sexually and gender fluid. For suburban youngsters — which a lot of the Kids as soon as have been — in what Bruce known as “parched landscapes,” their artwork was each an ideology and a revelation.

KITH utilized comparable ideas to their portrayals of girls. Though nominally primarily based in a British comedy custom, the principle motivation for taking part in ladies, as Bruce famous, was to attract from their very own lives and relationships and replicate the folks round them: “we’re playing our girlfriends or moms or, in the case of Kathie the secretary, my sister.”

In positing heteronormative masculinity as the opposite quite than the usual, they partly mirrored the gender politics of youth tradition on the time: male different rock stars like Kurt Cobain and Evan Dando wore clothes onstage or in magazines and impressed a self-reflexive, and self-conscious, relationship with masculinity. KITH’s efficiency of gender may need gestured towards the identical self-conscious masculinity in some instances, however they have been nearer to Riot Grrrl than grunge boy. They prevented the entice of compensatory male feminism by way of performances that destabilized gender binaries and the class of gender itself. “BECAUSE,” as Bikini Kill declared within the 1991 Riot Grrrl Manifesto, “we don’t wanna assimilate to someone else’s (boy) standards of what is or isn’t.”

Their embodiment of girls and female qualities reifies Simone de Beauvoir’s well-known assertion from The Second Sex, “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” An award given to KITH by a Canadian ladies’s media watch group within the early ’90s attests to what Judith Butler calls “the tenuousness of gender ‘reality,’” explaining why a bunch of cis males may conceivably current as convincing ladies to female-identifying viewers — and why they arguably succeeded as brokers of feminism. In the ’90s The Kids within the Hall was among the many solely exhibits that encompassed a spread of people, and portrayed ladies who fall outdoors of bodily or social norms, or heterosexual tropes, as something aside from pejorative stereotypes. (Even with a endless stream of exhibits right now, not a lot has modified.)

In later seasons, intercourse employees Jocelyn and Mordred (performed by Dave and Scott, respectively) offered a self-possessed, feminist foil to the anonymous, clueless cops performed by Mark and Bruce. More than simply inverting normative gender and sociopolitical roles, the characters reinforce the present’s outsider voice and its solidarity with that of its viewers. Their depth was enhanced by their shut friendship, unique of males (apart from their lovable “pimp,” Rudy, performed by Kevin), and poignantly positioned one of many present’s most real bonds between ladies outdoors of standard society, in distinction with the customarily fraught friendships or familial relationships of characters occupying mainstream milieus.

Other ladies had comparatively mundane lives, however for probably the most half they have been practical and relatable. The Kids touched — and nonetheless contact — on subjects starting from body shaming to sexual coercion with out making gentle of them and fleshed out “types” that not often acquired greater than a gloss in well-liked tradition: the high-strung profession girl, Nina; sympathetic mother Fran; lovelorn teen Melanie; gossiping secretaries Cathy and Kathie.

In distinction to Jocelyn and Mordred, the intercourse employees in season one’s French arthouse parody “Hotel La Rut” stay ciphers. The deadpan have an effect on intentionally flattens the melodrama. They emphasize the stylization by way of avant-garde filmic gadgets: for example, a mirror and window create frames inside frames that seize the 2 ladies, Silvee (Mark) and Michelle (Scott), and visually double the artifice of their performances. The Brechtian denaturalization of gender is underscored by the ladies’s androgynous our bodies, even because the actors exaggerate the gendered dynamic between the languid prostitutes and Dave’s smug French painter, who intrudes on their cloistered world. The ladies compose themselves as objects of the gaze — redoubled by Silvee, who gazes at herself within the mirror — mired in a haze of ennui. The sketch original a distinctly queer intimacy by way of the doubling and bodily contact between the ladies, and thru the violence of the male presence inside their softly female realm: Dave’s in addition to Tony’s, the absent however psychologically consuming man on the heart of the joke.

“Hotel La Rut” was a one-off sketch within the unique sequence (charmingly resurrected for the Prime Video present) however its artifice attracts consideration to the troupe’s numerous types of masquerade. In unmooring themselves from the strictures of prescribed gender identification, they might prolong the ideas of “drag” into polyvalent and hybrid characters that freely intermingle “male” and “female” signifiers (see, for example, “Womyn,” “Body Conscious,” or, extra fluidly, Mark enjoying a model of himself in “Confession” from the 1988 pilot).

At their most excessive, characters’ transgressive and polyvalent qualities landed them within the spheres of the grotesque and carnivalesque. Even small touches, just like the striped and patterned robes and pajamas worn by sanitarium escapees the Sizzler Sisters (Kevin and Dave), counsel these inverted worlds: In the Middle Ages artists typically portrayed minstrels and jesters in patterned or parti-color clothes, and outsider figures like foot-soldiers and executioners wore stripes. But these classes achieved their fullest expression in characters that merge the human world with the pure or animal world, Bruce’s Cabbage Head and Mark’s Chicken Lady.

Cabbage Head, a sleazy lounge-lizard kind who has cabbage leaves instead of hair, weaponizes his hybridity to elicit sympathy — and sympathy intercourse — from ladies (he’s the “king of the mercy fuck”). The absurdist tackle a typical situation of sexual predation throws its outlandishness into aid: “I don’t think that would have been funny if I was just … hitting on women with these lines and saying, ‘I had a bad childhood.’ There was something about the surreality,” Bruce instructed me. “I think that’s just automatic: How did that hit me? I don’t know. He’s got a cabbage for a head. Well, let’s go with that.”

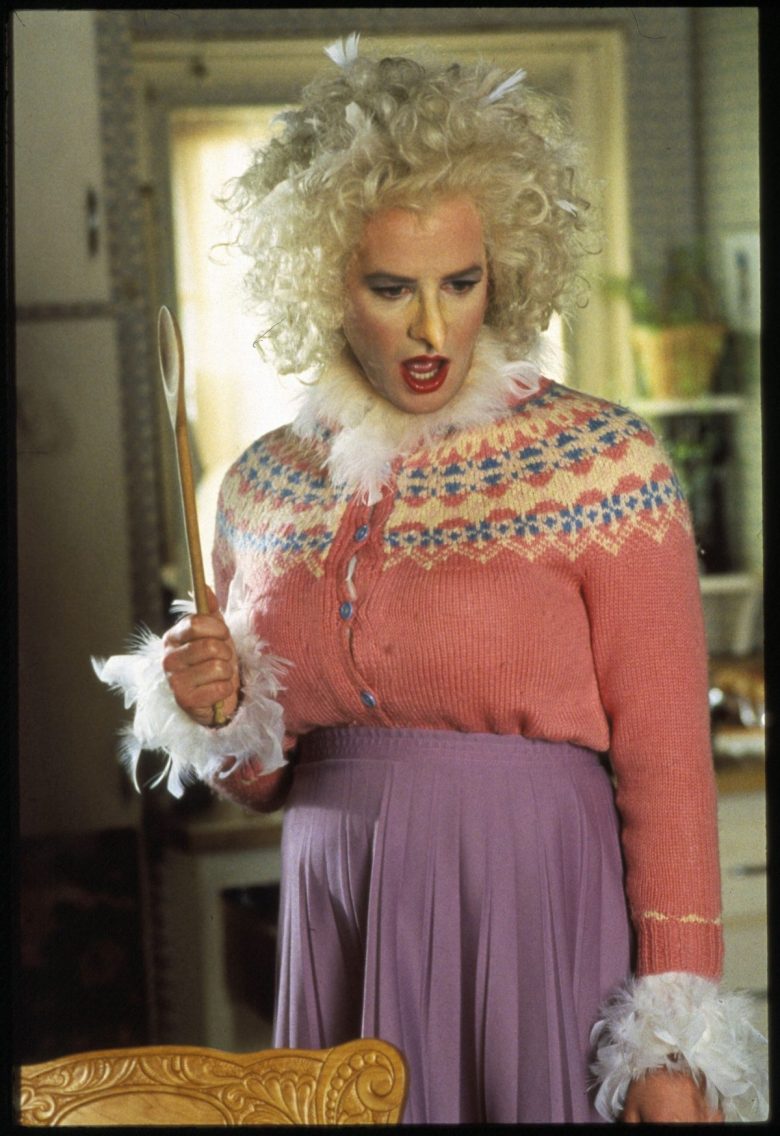

In distinction to Cabbage Head’s poisonous masculinity, bawdy Chicken Lady is a component and parcel of the Rabelaisian comedian grotesque and its joyfully unruly physique and appetites. Her specific hybridity has roots in commedia dell’arte’s exaggerated gestures and avian masks (though the particular inspiration for the character was apparently Tod Browning’s 1932 movie Freaks). At the identical time, she’s a genuinely sympathetic determine; as audiences are reminded in multiple sketch, her hybridity has relegated her to perpetual outsider standing.

Chicken Lady, her pal the Bearded Lady (Kevin), and even the Sizzler Sisters symbolize the outsiders for whom KITH have created a protected and inclusive house. Yet of their carnivalesque splendor, in their very own worlds throughout the present’s already alternate world, they’re impervious to the labels thrust upon them by well mannered society. Their comedian transgressions are layered with social and organic transgressions that shadow the comedic bathos with the pathos of actual life.

In his 1963 research The Grotesque in Art and Literature, Wolfgang Kayser defines the grotesque because the “estranged world.” Kayser writes that the grotesque “does not constitute a fantastic realm of its own …. The grotesque world is — and is not — our own world. The ambiguous way in which we are affected by it results from our awareness that the familiar and apparently harmonious world is alienated under the impact of abysmal forces, which break up and shatter its coherence.”

The passage is about Pieter Bruegel the Elder, however the ideas, and Kayser’s declare that Bruegel “wanted to portray the absurd in all its absurdity,” completely describe KITH’s “estranged worlds” of middle-class suburbia and company tradition, in all their social mores, hypocrisies, and horrific abuses (see Kevin’s autobiographical sketch “Daddy Drank”). In the ’90s KITH’s arch portrayals of businessmen, just like the “Geralds,” converged with the period’s contempt towards “selling out.” Underscored by characters like Bruce’s insurgent financial institution worker (“Fuck the bank I work for!”) or the present’s most well-known vigilante, Mark’s Head Crusher, this cemented their standing as anti-establishment and anti-authority voices in a society populated by drunk dads, assholes, and pricks.

At their darkest are masterworks of fine-tuned satire just like the pilot’s closing sketch, “Reg,” written by Kevin, Dave, and Bruce. The troupe play a fugitive band of brothers gathered round a fireplace (in a child carriage), reminiscing about their useless pal Reg. It all seems like a 20-something Stand By Me till it emerges that they ritualistically murdered him. Still, they miss him: They want that they had mentioned extra once they had the prospect they usually surprise the place his soul is. “There are some scenes that really are the soul of the troupe,” Bruce commented of the sketch. “There’s something about that, the five of us agreeing that this is a great idea.”

Alongside what it says in regards to the troupe’s bond, “Reg” illustrates a theme that recurred all through the sequence: the rupture between purpose and actuality, and the bounds of reconciling them. Kayser posited that Bruegel secularized Bosch’s Christian Hell to painting a world that “permits of no rational or emotional explanation.” Without the ethical compass of faith that gave that means to Bosch’s “Garden of Earthly Delights,” Kayser argued, Bruegel’s hellish landscapes strip the veneer of purpose from the world.

In the same means, KITH lay naked the absence of purpose and current a world “alienated under the impact of abysmal forces.” They share much less with what a 2000 New York Times article known as ’90s “hipster meta-humorists” than with the gallows humor of World War I literature, from authors shocked into cynicism by trendy struggle and dying. Beyond the distractions of life that chatter away of their scenes is an existential No Man’s Land; the Kids had been there and are available again.

“The men whom I knew … were tough; they knew how to fight and suffer with comic grace,” wrote Esther Newton in Mother Camp: Female Impersonators in America (1972). If the 2022 sequence is a reminder of the Kids within the Hall’s genius, it’s a reminder as effectively of the capability of 5 White males, principally straight and from the suburbs, to fiercely de-center themselves, and the straight male perspective — to take the offended younger man they every embodied and unsex him. Their toughness, just like the performers to whom Newton refers, is based on otherness as an crucial. For the era they most replicate, they represented the one viable path ahead. In the preface to Mother Camp, Newton writes: “If we really examine ‘normalcy’ we may choke on what we bring up.”

Fuck the system. Fuck normalcy. Fuck the financial institution.